Building internal tech systems vs providing ‘whole’ services

As we go about redesigning public services to be clearer, simpler and faster, we sometimes hear things like, ‘civil servants are users too.’ And of course they are.

Internal users in many kinds of organisations can be inhibited by the systems they work with, particularly those working on the frontline or behind the scenes.

We all talk about ‘users’, but there are many kinds of people involved in a service. When we redesign larger services to better achieve policy intent and meet user needs, we have to understand important distinctions such as:

what the end user is trying to do and what their needs are

what the people involved in delivering or providing a service are doing and why

what it’s like to be the user of an internal product or system

what actually needs to happen behind the scenes – not just what’s currently happening

When we conflate what end users need with what people providing a service want, we end up with poorly designed, inefficient services that aren’t easy to use.

Equally, when we confuse what needs to happen with how something is done today, we make the mistake of designing ‘digital’ versions of the same thing without addressing the problems.

The aim is for services that are effective and efficient, that are fundamentally better and easier to change in the future.

Key questions we need to ask are:

are we redesigning an internal system that has users?

is this system part of a wider service for end users?

If it is, we need to look at the wider service that’s delivered by people behind the scenes so we don’t just redesign the existing system.

The perspective we take can result in very different outcomes.

Design based on what actually needs to happen

Let’s say we’re redesigning a casework system. We might watch people using the current system to see what makes it difficult or easy to use. Policy might work closely with the product team to make sure the system reflects the right criteria and that internal users apply the rules correctly and consistently.

We might watch caseworkers use prototypes of the new system to learn what works and doesn’t work. We could list the things the system has to do and we might apply the style guide for an organisation e.g. GOV.UK style guide.

While there are lots of positives with this approach, there’s a good chance we’d essentially design the same system again based on how things currently work, although it might be easier to use.

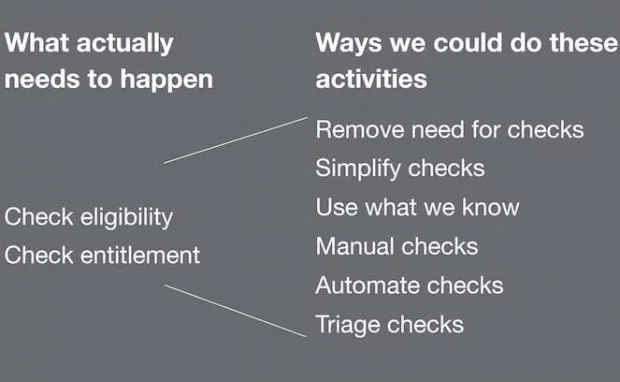

Let’s run that scenario again but look at what needs to happen. Rather than talk about a ‘casework system’ we’d look at the wider service. This part of it is there to decide if someone gets permission to do something.

We’d see that the activities behind the scenes are:

comparing data against set criteria

assessing suitability

assessing eligibility

making a decision

recording an outcome

notifying the user

These activities are the things that will still likely need to happen even in 10 years’ time, whether it’s a human doing this, a computer, artificial intelligence or some other way we haven’t imagined yet.

Perhaps we’d see that this activity takes significant time and resources because of the high volumes and what currently happens. Waiting for an answer can be really difficult for end users, who then spend time trying to find out what’s happening – and government, or any large organisation bears the cost of that.

Even if we can make a casework system that’s easier and faster to use, building something that someone still has to manually operate won’t necessarily solve these problems and it probably won’t scale or allow us to radically cut the time it takes to make a decision.

If we considered what actually needs to happen, we’d talk about the project in terms of ‘how we make decisions about an application more effectively and efficiently’, not ‘casework systems’.

We could find practical ways to measure what we mean by this and make a clear and simple statement about what we’re aiming for – the time it should take or the resources involved – to make a decision.

By rethinking policy, process, content or technology, we open ourselves up to the many possible solutions we have.

A few of these are:

simplify some of the criteria we’re using to reduce effort

explain more simply and clearly what we need – and why

design an application that works better for different scenarios across many services by looking at unchanging activities such as assessing suitability and eligibility, rather than on current workflow

gather data by going to original sources and verifying it digitally rather than working with paper copies

use information from existing digital records

use computers to compare data against set criteria automatically, where possible and appropriate

check eligibility and suitability as an application is being filled in rather than after it’s submitted

use computers to identify complex cases that need people to evaluate them in depth and train then use algorithms to learn how to improve effectiveness or efficiency

Thinking through these options takes many disciplines, including specialists in policy, user research, operations, security, legal, data, delivery and technology. The right approach is to learn which combination of these options will work best and to better understand what the challenges are.

The best service is where no one needs to do anything

To use resources effectively and efficiently, we need to avoid simply build digital-and-slightly-improved versions of the same old systems or workflow. Teams have the biggest impact when focused on clearly identified problems and outcomes, not just on re-building a system.

When there is a logical and considered rationale for doing something tactical to buy us time, we still need to work out how to remove current constraints for the future.

And specialist digital teams need room to fundamentally rethink the best ways of delivering the outcomes we’re after and measure progress on that basis.